ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY

Nella mia vita ho fatto un po' di tutto: teatro, teatro mimico, pantomima, musica, sono stato attore, decoratore, scenografo, costumista... regista, sì, sì, il cinema! A che cosa serve tutto questo, perché lo faccio? Sono immortale!

Che tipo di rapporto hai con il tuo lavoro?

Che tipo di rapporto hai con il tuo lavoro? L' uomo serve innanzitutto a se stesso, al suo narcisismo...tutto ciò che si fa, prima o poi scompare e lascia dentro di noi un' enorme depressione...tramite le arti ho cercato una "aspirina metafisica" ed ho seguito i corsi di Gurdjieff, almeno per tre anni. Il mio monastero in Messico era accanto ad un immondezzaio pieno di mosche. Durante le meditazioni te ne ronzavano intorno a decine e se muovevi anche solo il viso il Maestro ti colpiva.Il mio grande maestro furono le mosche!

L' uomo serve innanzitutto a se stesso, al suo narcisismo...tutto ciò che si fa, prima o poi scompare e lascia dentro di noi un' enorme depressione...tramite le arti ho cercato una "aspirina metafisica" ed ho seguito i corsi di Gurdjieff, almeno per tre anni. Il mio monastero in Messico era accanto ad un immondezzaio pieno di mosche. Durante le meditazioni te ne ronzavano intorno a decine e se muovevi anche solo il viso il Maestro ti colpiva.Il mio grande maestro furono le mosche!Ho cercato ovunque, anche in campo esoterico; alla fine mi resi conto di essermici ammalato, stavo diventando nevrotico. La risposta giunse in quegli anni, e fu una illuminazione: il compito dell' arte è curare: curare la vita emozionale dello spettatore. La pratica di cura si sviluppa tramite la guarigione dell' aspetto emozionale, emotivo, sessuale o di ogni altro tipo di infermità, guarigione che avviene grazie ai tarocchi o lo studio dell' albero genealogico.

Ho creato una terapia, ma non basata su una scienza o un indirizzo universitario: la mia terapia ha le sue origini all' interno dell'arte.

Ho diretto circa cento opere teatrali. L' unica cosa che non ho fatto è stato cantare il tango... avrei tanto voluto cantare il tango. Mia madre era una cantante d' opera e le capitava di innamorarsi di cantanti di tango: mi portava sempre ad ascoltarli... ma non ho mai potuto cantare.

Freud veniva dalla scienza, era medico, io invece vengo dall' arte, anche se mi sono proposto di acquisire le stesse conoscenze che possiedono gli psicanalisti. Non dico che la psicomagia sia migliore della psicanalisi: dico solo che le è vicina. Ma, invece di esigere molti incontri, alla psicomagia ne basta uno: lei è la via più breve.

Nello Zen c'è questo tipo di concetto: puoi meditare vent' anni e forse arrivi all' illuminazione; però a volte si trova una via più breve, anche nello Zen.

Nello Zen c'è questo tipo di concetto: puoi meditare vent' anni e forse arrivi all' illuminazione; però a volte si trova una via più breve, anche nello Zen.Il mio Maestro Zen in Messico mi fece meditare sette giorni in ginocchio senza dormire... avevo le ginocchia completamente rovinate. C' era un assistente di Karate messicano che il sesto giorno mi saltò addosso, cominciando a picchiarmi ben bene. Mi trascinò davanti al Maestro che, vestito da giapponese, mi disse, biascicando uno spagnolo quasi incomprensibile: "Non comincia, non finisce, che cos' è?". "Merda!", dico io, perchè mi fa una domanda del genere? Che gli rispondo? E' Dio? Lo Spirito Santo? Sono io? L' infinito? Perchè mi chiede una cosa così imbecille? A quel punto fece suonare un gong e tutta la scuola seppe che avevo avuto un fallimento.

L' intellettuale deve imparare a morire. Questa è la via rapida, la psicomagia è una via rapida nei confronti di qualsiasi problema. Gurdjieff faceva fare ad alcune persone cose che non avevano mai fatto; anche Castaneda: prendeva un direttore di un giornale e lo metteva a vendere giornali all' angolo. Lo stesso Castaneda lavorò per due anni a una pompa di un distributore di benzina: aveva capito che se si cambia il circuito entro cui gira la vita, cambia anche la vita stessa, e li' c'è la cura. Lacan disse che l' inconscio è un linguaggio: tutti coloro che fanno teatro sanno invece che l' inconscio è un atto. Esprimere coi gesti una serie di concetti che non si dirigono verso l' intelletto, ma si rivolgono all' inconscio: questo è vero teatro. E la psicomagia è un atto teatrale, poetico, a volte terribile, a volte difficile, però cura. Ogni problema è personale; non esistono malattie uguali, sono solo simili.

Quando ho il raffreddore sono contento perchè non lavoro, anzi: mischio il mio muco ad una tintura vegetale e ci dipingo. Il raffreddore è molto artistico!

Al mio agente letterario Marcel Casanova avevano predetto che

qualcuno vicino a lui sarebbe morto e che gli sarebbe costato un bel mucchio di soldi. Ogni predizione fa male. Nostradamus ha un linguaggio difficile da interpretare chiaramente: per questo, a posteriori, si crede che abbia previsto ogni avvenimento. Ogni predizione è come una maledizione: anche se non ci credi ti ritrovi preoccupato. L' unica strada per liberarsi è fare che la predizione si avveri.

qualcuno vicino a lui sarebbe morto e che gli sarebbe costato un bel mucchio di soldi. Ogni predizione fa male. Nostradamus ha un linguaggio difficile da interpretare chiaramente: per questo, a posteriori, si crede che abbia previsto ogni avvenimento. Ogni predizione è come una maledizione: anche se non ci credi ti ritrovi preoccupato. L' unica strada per liberarsi è fare che la predizione si avveri.Così dissi a Casanova di andare a casa, chiudere le finestre e spruzzare l' insetticida. Sicuramente avrebbe visto morire accanto a se' almeno una mosca! Dissi di prendere un biglietto da venti pesetas e aggiungerci sei zeri. Infine ordinai di prendere mosca e soldi e sotterrarli. Così la predizione si era avverata.

Ho curato l' intera Francia seguendo esempi del genere. Questa nazione ora è nel panico perchè il mago Paco Rabanne, leggendo Nostradamus, ha previsto che l' undici Agosto cadrà un satellite su Parigi uccidendo milioni di persone. Ogni predizione porta dietro di se' delle conseguenze: i giornali ne parlano, i turisti non vengono, causando un blocco economico. Diversi giornalisti sono venuti da me per questo motivo. Allora ho raccontato loro un evento: un Guru disse alla sua gente che l' indomani il sole non sarebbe sorto. Il popolo passò la notte senza dormire, soffrendo e piangendo. Ma giunse il mattino, e la gente si recò dal maestro per gioire con lui, ma lui era morto.

Io dissi ai giornalisti che Paco Rabanne sarebbe morto l' undici di Agosto.

Questo metodo l' ho imparato da una barzelletta ebrea: Sara chiese a suo marito Abramo perchè non riuscisse a dormire. Quando seppe che doveva dei soldi a Mosè, Sara aprì la finestra e gridò: "Mosè! Mio marito domattina non potrà pagarti, perchè non ha i soldi!". Rientrando, Sara disse ad Abramo: "Adesso smettila di preoccuparti, e vai a dormire: sarà Mosè, stanotte, a non chiudere occhio!".

Se qualcuno ti manda una maledizione, tu puoi trasformarti in uno specchio e rimandare la maledizione a chi te l' ha lanciata.

Il nostro albero genealogico è pieno di predizioni, per esempio come quando i nostri avi dicevano alle loro figlie: "Tu sei bella, ti sposerai, e basta!". Questa è una maledizione! Siamo noi stessi che dobbiamo benedirci. Sto scrivendo un libro sulla psicomagia, ed è un libro molto lungo, perchè è un argomento difficile da esaurire in pochi minuti.

Come mai non ha più fatto cinema?

Per due motivi: uno intellettuale e uno economico. Il cinema a poco a poco si è trasformato in industria. La produzione negli Stati Uniti ha un costo di cento milioni di dollari; è una cifra che si può racimolare in un mese. Mentre due milioni di dollari, che mi basterebbero, non sono ancora riuscito a trovarli, da otto anni a questa parte.

Per secondo, faccio un film quando ho qualcosa di nuovo da dire. Da Gennaio prossimo ne vorrei cominciare un altro. Nella mia vita ho fatto molte cose, ed ora sto facendo poesia. Fellini ha fatto "Otto e mezzo" ed ha realizzato l' angoscia del regista; io vorrei realizzare quella del poeta, profondamente interiore. Il teatro ha incorporato elementi della danza; il cinema deve assorbire quelli del teatro-danza. Lo sapete come ho conosciuto Fellini? Durante una conferenza (simile a questa) per la presentazione di "Santa Sangre" c'era anche Fellini che mi invitò a vedere le riprese per "La voce della luna"; io vado, di notte, in un campo aperto: in fondo c' era la figura di un uomo grande con un cappello in mano.Vado, timido, verso di lui, che mi riconosce. Quando gli giungo davanti gli dico: "Papà!". Poi cominciò a piovere forte, noi iniziammo a correre per trovare riparo, e finì lì. Così andò il primo dialogo con Fellini!

Per secondo, faccio un film quando ho qualcosa di nuovo da dire. Da Gennaio prossimo ne vorrei cominciare un altro. Nella mia vita ho fatto molte cose, ed ora sto facendo poesia. Fellini ha fatto "Otto e mezzo" ed ha realizzato l' angoscia del regista; io vorrei realizzare quella del poeta, profondamente interiore. Il teatro ha incorporato elementi della danza; il cinema deve assorbire quelli del teatro-danza. Lo sapete come ho conosciuto Fellini? Durante una conferenza (simile a questa) per la presentazione di "Santa Sangre" c'era anche Fellini che mi invitò a vedere le riprese per "La voce della luna"; io vado, di notte, in un campo aperto: in fondo c' era la figura di un uomo grande con un cappello in mano.Vado, timido, verso di lui, che mi riconosce. Quando gli giungo davanti gli dico: "Papà!". Poi cominciò a piovere forte, noi iniziammo a correre per trovare riparo, e finì lì. Così andò il primo dialogo con Fellini!Che cosa racconterebbe ancora di sé con questo suo tipico modo di affabulare?

Beh.. Ho messo in scena circa centocinquanta opere teatrali in Messico tratte da Jonesco, Artaud... tutto! Ho fatto cinema, tre, quattro, cinque, sei films, romanzi, racconti, fumetti, già! Per il fumetto ho ricevuto la "Pantera Nera"! Ho anche diretto Maurice Chevalier ... faccio tutto! Ho inventato l' happening prima che si chiamasse così.

Nella vita ci sono molti tipi di malattie... depressioni, nevrosi... ma il motivo è sempre lo stesso: mancanza di bellezza. Perchè quando manca la bellezza non si può pretendere di essere umani. Il meraviglioso è un problema difficile, affatto semplice. Gli architetti moderni pensano di fare strutture belle, ma sono solo criminali; non conoscono la bellezza, pensano che sia qualcosa di intellettuale, di razionale, ma il razionale non è buono.. Perchè il razionale è soltanto una parte dell' essere umano: esiste una piramide scura, grande, che sta sotto e rappresenta l' inconscio ed una opposta, speculare, luminosa, che rappresenta il subcoscio. Sta nel mezzo il problema: per ottenere la bellezza bisogna aprire una porta tra il subconscio e l' inconscio. Ed è molto difficile, perchè la verità è difficile da ottenere: la filosofia ha sempre cercato la verità, ma ha ottenuto solo dei fallimenti perchè non si può definire l' essenza di Dio come non si può ottenere la verità. E' impossibile, al di sopra delle possibilità dell' uomo. Però la verità proietta una luce, che è la bellezza. Ho mollato la filosofia ed ora sto all' Università... sono colpevole, me ne scuso. Ho lasciato la folosofia per la poesia... cercavo la bellezza, ma non ho mai detto a nessuno, all' inizio, chefacevo poesia, perchè mi vergognavo. Un giorno, viaggiando, ho sbagliato strada e mi sono ritrovato a Firenze, alla libreria City Lights, del signor Bertoldi, proprio nel giorno dell' inaugurazione e vedo Berlinghetti, quello dei tempi del teatro panico, che stava leggendo un suo libro di poesie, e allora ho detto che anch' io ne avevo uno, perchè non leggiamo anche il mio? Nella poesia ho anche cercato l' amore, ma non l' amore di un uomo per una donna, o per il corpo di una donna, ma quello tra anima e anima.

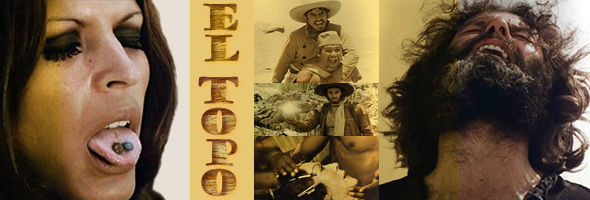

Nella vita ci sono molti tipi di malattie... depressioni, nevrosi... ma il motivo è sempre lo stesso: mancanza di bellezza. Perchè quando manca la bellezza non si può pretendere di essere umani. Il meraviglioso è un problema difficile, affatto semplice. Gli architetti moderni pensano di fare strutture belle, ma sono solo criminali; non conoscono la bellezza, pensano che sia qualcosa di intellettuale, di razionale, ma il razionale non è buono.. Perchè il razionale è soltanto una parte dell' essere umano: esiste una piramide scura, grande, che sta sotto e rappresenta l' inconscio ed una opposta, speculare, luminosa, che rappresenta il subcoscio. Sta nel mezzo il problema: per ottenere la bellezza bisogna aprire una porta tra il subconscio e l' inconscio. Ed è molto difficile, perchè la verità è difficile da ottenere: la filosofia ha sempre cercato la verità, ma ha ottenuto solo dei fallimenti perchè non si può definire l' essenza di Dio come non si può ottenere la verità. E' impossibile, al di sopra delle possibilità dell' uomo. Però la verità proietta una luce, che è la bellezza. Ho mollato la filosofia ed ora sto all' Università... sono colpevole, me ne scuso. Ho lasciato la folosofia per la poesia... cercavo la bellezza, ma non ho mai detto a nessuno, all' inizio, chefacevo poesia, perchè mi vergognavo. Un giorno, viaggiando, ho sbagliato strada e mi sono ritrovato a Firenze, alla libreria City Lights, del signor Bertoldi, proprio nel giorno dell' inaugurazione e vedo Berlinghetti, quello dei tempi del teatro panico, che stava leggendo un suo libro di poesie, e allora ho detto che anch' io ne avevo uno, perchè non leggiamo anche il mio? Nella poesia ho anche cercato l' amore, ma non l' amore di un uomo per una donna, o per il corpo di una donna, ma quello tra anima e anima.  Dopo c' è stato il corpo, sicuramente, ma non prima. Ho cercato una poesia non ideologica, perchè la bellezza non ha un' ideologia politica... quando parlo di poesia mi si alzano le sopracciglia, ed io le abbasso. Ho iniziato col surrealismo, col dettato automatico; Quando apri la porta all' inconscio, questo dice sempre qualcosa... Ho scritto su di me, su che cosa immaginerei se fossi libero, cosa penserei... perchè c' è una censura del pensiero... che cosa si sente se si è liberi? Ho conosciuto una donna con un problema: odiava il suo bambino. Un grosso problema, non sapevo che fare. Lei cercava di trattenersi, ma non ci riusciva. Le dissi che la prima cosa da fare era confessarsi quel sentimento, che era libera di farlo. C' era una donna, filosofa, col marito anche lui filosofo, con in più un' amante. Lei era gelosa, io le dissi di accettare la gelosia, e lei mi disse che non poteva, chè era filosofa... ed io le dissi che invece poteva farlo, che era libera di permettersi qualsiasi tipo di sentimento... perché se sei libero a livello sessuale puoi permetterti qualsiasi cosa... non parlo del "fare", ma del sentimento. Ho un bel pensiero su questo, non contro il Papa, bello... jo voj a ver el Papa, e non credo, de pronto el Papa apparece e la Papessa apparece, e quattri bambini e il figlio e tutta la famillia Con dodice mano me benedice, la famiglia sacra, che maraviglia nel Vaticano una Famiglia Sacra! Quali azioni posso permettermi? Non il crimine, perchè con il crimine si distrugge, ma quali azioni positive posso permettermi? Non perchè sono in Italia, davvero, lo giuro, ma secondo me la vera poesia è nata con Marinetti, perchè lui ha detto che la poesia è un atto: aveva cercato l' atto poetico. Prima dell' happening, in una trasmissione televisiva, ho comprato un pianoforte, e mi sono detto che in messico piacciono molto gli artisti e i toreri... lo strumento del torero è il toro, il piano può esserlo per un artista... come il matador dopo aver giostrato col toro lo uccide, così anche l' artista dopo lo spettacolo può distruggere il suo strumento. Pensavo che solo poche persone l' avrebbero visto, dato che la mia era una piccola emittente televisiva. Mentre il musicista suonava io cominciai a distruggere il piano con un martello; mi ci volle un' ora e mezzo, ma alla fine tutto il Messico mi aveva visto! Tra le cinquemila chiamate al centralino telefonico ci fu quella del Ministro dell' educazione che mi chiese, indignato, come avevo potuto fare una cosa del genere. Fu uno scandalo. Avevo creato l' happening. Un atto poetico. Perchè ho fatto una cosa del genere? Forse per proteggere l' industria del piano... vi ho detto questo perchè sono buono. Da piccolo una volta uscii in strada con una banana in mano. Il mio film, "El topo", è diventato un mito negli Stati Uniti, ma per me la mia vita non è cambiata. Andai in un ristorante il cui padrone era un argentino che faceva il catch, legeva le carte ed era completamente dominato dal suo psicanalista... un mostro! Io ero con una donna grossa, cheera diventata mezza matta con la scintologia... Troika... dopo un po' che ero seduto arriva un' altra donna che mi chiede se volevo conoscere Castaneda. "Certo che lo voglio!" dico io. "E' qui" fa lei, "può venire al suo tavolo se lo desidera". "No, no, vado io!". Stava mangiando un bisteccone con vino, il mago! Mi chiese se volevo vedere con lui "El topo" , e dopo che gli dissi di sì, ci lasciammo d' accordo che sarebbe venuto lui al mio albergo l' indomani mattina. Il giorno dopo, a cinque minuti a mezzogiorno, mi telefona Castaneda dicendomi: "Perdonami, sono cinque minuti in anticipo: posso salire?".Era molto educato. In "Psicomagia" racconto l' incontro con lui. Ci deve essere un motivo per cui ci siamo incontrati: è il destino che lo ha voluto. Al tempo non praticavo ancora la psicomagia. Cercavo, cercavo qualcosa. Ad un certo punto mi venne un attacco di diarrea. Con tutta l' acqua che bevi in Messico ti viene la diarrea... è la vendetta di Moctectzuma! Il giorno seguente avevo in programma di farmi operare al fegato da Pachita. Gli dissi di venire, ma lui non venne. Andai a chiedere di lui al suo hotel, l' "Holiday Inn", e scoprii che era partito con Troika! Terribile! Questa è la storia dell' incontro con Castaneda.

Dopo c' è stato il corpo, sicuramente, ma non prima. Ho cercato una poesia non ideologica, perchè la bellezza non ha un' ideologia politica... quando parlo di poesia mi si alzano le sopracciglia, ed io le abbasso. Ho iniziato col surrealismo, col dettato automatico; Quando apri la porta all' inconscio, questo dice sempre qualcosa... Ho scritto su di me, su che cosa immaginerei se fossi libero, cosa penserei... perchè c' è una censura del pensiero... che cosa si sente se si è liberi? Ho conosciuto una donna con un problema: odiava il suo bambino. Un grosso problema, non sapevo che fare. Lei cercava di trattenersi, ma non ci riusciva. Le dissi che la prima cosa da fare era confessarsi quel sentimento, che era libera di farlo. C' era una donna, filosofa, col marito anche lui filosofo, con in più un' amante. Lei era gelosa, io le dissi di accettare la gelosia, e lei mi disse che non poteva, chè era filosofa... ed io le dissi che invece poteva farlo, che era libera di permettersi qualsiasi tipo di sentimento... perché se sei libero a livello sessuale puoi permetterti qualsiasi cosa... non parlo del "fare", ma del sentimento. Ho un bel pensiero su questo, non contro il Papa, bello... jo voj a ver el Papa, e non credo, de pronto el Papa apparece e la Papessa apparece, e quattri bambini e il figlio e tutta la famillia Con dodice mano me benedice, la famiglia sacra, che maraviglia nel Vaticano una Famiglia Sacra! Quali azioni posso permettermi? Non il crimine, perchè con il crimine si distrugge, ma quali azioni positive posso permettermi? Non perchè sono in Italia, davvero, lo giuro, ma secondo me la vera poesia è nata con Marinetti, perchè lui ha detto che la poesia è un atto: aveva cercato l' atto poetico. Prima dell' happening, in una trasmissione televisiva, ho comprato un pianoforte, e mi sono detto che in messico piacciono molto gli artisti e i toreri... lo strumento del torero è il toro, il piano può esserlo per un artista... come il matador dopo aver giostrato col toro lo uccide, così anche l' artista dopo lo spettacolo può distruggere il suo strumento. Pensavo che solo poche persone l' avrebbero visto, dato che la mia era una piccola emittente televisiva. Mentre il musicista suonava io cominciai a distruggere il piano con un martello; mi ci volle un' ora e mezzo, ma alla fine tutto il Messico mi aveva visto! Tra le cinquemila chiamate al centralino telefonico ci fu quella del Ministro dell' educazione che mi chiese, indignato, come avevo potuto fare una cosa del genere. Fu uno scandalo. Avevo creato l' happening. Un atto poetico. Perchè ho fatto una cosa del genere? Forse per proteggere l' industria del piano... vi ho detto questo perchè sono buono. Da piccolo una volta uscii in strada con una banana in mano. Il mio film, "El topo", è diventato un mito negli Stati Uniti, ma per me la mia vita non è cambiata. Andai in un ristorante il cui padrone era un argentino che faceva il catch, legeva le carte ed era completamente dominato dal suo psicanalista... un mostro! Io ero con una donna grossa, cheera diventata mezza matta con la scintologia... Troika... dopo un po' che ero seduto arriva un' altra donna che mi chiede se volevo conoscere Castaneda. "Certo che lo voglio!" dico io. "E' qui" fa lei, "può venire al suo tavolo se lo desidera". "No, no, vado io!". Stava mangiando un bisteccone con vino, il mago! Mi chiese se volevo vedere con lui "El topo" , e dopo che gli dissi di sì, ci lasciammo d' accordo che sarebbe venuto lui al mio albergo l' indomani mattina. Il giorno dopo, a cinque minuti a mezzogiorno, mi telefona Castaneda dicendomi: "Perdonami, sono cinque minuti in anticipo: posso salire?".Era molto educato. In "Psicomagia" racconto l' incontro con lui. Ci deve essere un motivo per cui ci siamo incontrati: è il destino che lo ha voluto. Al tempo non praticavo ancora la psicomagia. Cercavo, cercavo qualcosa. Ad un certo punto mi venne un attacco di diarrea. Con tutta l' acqua che bevi in Messico ti viene la diarrea... è la vendetta di Moctectzuma! Il giorno seguente avevo in programma di farmi operare al fegato da Pachita. Gli dissi di venire, ma lui non venne. Andai a chiedere di lui al suo hotel, l' "Holiday Inn", e scoprii che era partito con Troika! Terribile! Questa è la storia dell' incontro con Castaneda.Le è dispiaciuto non poter girare "Dune"?

Non direi: io penso che il fallimento non esista. E' solo un cambio di strada. Il fallimento è solo l' inizio di qualcosa di nuovo, non è lo scopo. Un commerciante di armi, uno degli uomini più sicchi di Francia (era povero fino a cinquant' anni) disse che nella vita per avere successo bisogna fallire almeno tre volte. Non ho fatto "Dune", ma ho avuto l' opportunità di conoscere molti personaggi tra cui basti Moebius, e di fare cinquanta libri di fumetti. Ho cambiato il mio cammino, dal cinema al fumetto. Punto! La vita è come una ruota, la ruota della Fortuna, che gira... dopo vent' anni ho fatto il "Meta barone" ed ho detto tutto ciò che avrei detto in "Dune", e Hollywood mi ha pagato molto bene per aver scritto la sceneggiatura. Sto influenzando il cinema, guadagno molto denaro... ed è per questo che ora sono con lui (con A: Bertoli, l' editore degli ultimi testi di poesia), perchè non guadagno: in cambio gli offro quindici giorni della mia vita, per la poesia... per l' avventura poetica. All' improvviso l' ho chiamato dicendogli che l' avventura poetica sarebbecominciata prima: "Vieni con me in Cile!". E ci siamo andati. Visto? Non si trattava di un fallimento!

Non direi: io penso che il fallimento non esista. E' solo un cambio di strada. Il fallimento è solo l' inizio di qualcosa di nuovo, non è lo scopo. Un commerciante di armi, uno degli uomini più sicchi di Francia (era povero fino a cinquant' anni) disse che nella vita per avere successo bisogna fallire almeno tre volte. Non ho fatto "Dune", ma ho avuto l' opportunità di conoscere molti personaggi tra cui basti Moebius, e di fare cinquanta libri di fumetti. Ho cambiato il mio cammino, dal cinema al fumetto. Punto! La vita è come una ruota, la ruota della Fortuna, che gira... dopo vent' anni ho fatto il "Meta barone" ed ho detto tutto ciò che avrei detto in "Dune", e Hollywood mi ha pagato molto bene per aver scritto la sceneggiatura. Sto influenzando il cinema, guadagno molto denaro... ed è per questo che ora sono con lui (con A: Bertoli, l' editore degli ultimi testi di poesia), perchè non guadagno: in cambio gli offro quindici giorni della mia vita, per la poesia... per l' avventura poetica. All' improvviso l' ho chiamato dicendogli che l' avventura poetica sarebbecominciata prima: "Vieni con me in Cile!". E ci siamo andati. Visto? Non si trattava di un fallimento!Ma quali sono le origini della psicomagia?

Ho cominciato coi tarocchi, cinquant' anni fa. Il tarocco è magnifico per aiutare la gente. Il mondo va male, io non posso cambiare il mondo, ma posso cominciare a cambiarlo. Così, ogni mercoledì leggo i tarocchi gratis: vado in un caffè e lì ascolto la gente. Sono vent' anni che lo faccio e ogni volta si forma una fila lunghissima. La psicanalisi non ha ragione nel sostenere che una volta individuato il problema e la sua fonte il paziente è guarito. No! Ci si rende solamente conto del problema, ma il problema non cambia. Bene. Che fare? Papà mi ha violentato nella culla. Ok, ma adesso che faccio? Continuerò a mangiare hot-dogs? La gente capisce che quando ha individuato il problema ha bisogno di un atto. Ci vuole qualcosa: un confronto, un atto simbolico, o quello che sia. Ho cominciato con piccoli consigli psicologici, piccole cose. Ecco la cura che detti a una ragazza: la tua famiglia deve riunirsi e tu devi andare alla riunione atteggiandoti a pappagallo -aiutandoti coi vestiti e col linguaggio- dimodochè tutti ti credano tale. Ci fu uno scandalo in famiglia, ma a lei fece molto bene! Il secondo "atto" fu: a una donna il suo ex-uomo aveva detto che non la voleva più vedere; e se le fosse venuto in mente di tornare da lui, badasse bene di farlo con la lingua a terra, per umiliazione.

Io le dissi di farsi fare una lingua finta e di andare da lui con quella.Il mio terzo atto, invece, lo commissionai ad un omosessuale, sieropositivo, che tendeva al suicidio. Diceva che lo psicanalista non riusciva a guarirlo. Non sapevo che pesci prendere... alla fine gli dissi che era un problema di sangue, e che doveva imparare che il sangue si può curare. Gli dissi di andare in un mattatoio con un grande thermos e chiedere a qualcuno il permesso di aiutarlo ad uccidere una vacca; poi di portarsi via tutto il sangue e di farcisi una doccia. Così fradicio, doveva montare su un pallone aerostatico con una foto di se' piccolo, e gettarla giù insieme a dei confetti. Mi guardò scioccato... ripeteva le mie parole dicendo: "E' impossibile! Dove lo trovo un pallone aerostatico?" " Se lo vuoi fare, lo fai", gli dissi. Poi incontrò una persona a cui raccontò tutto, persona che gli disse di essere il figlio del direttore del mattatoio. In seguito scoprì che i palloni aerostatici possono essere affittati da chiunque, ed è riuscito a compiere il suo meraviglioso atto panico. Non dico di avergli curato il sangue, ma la depressione se n'è andata, vive la sua sessualità con gioia, si è rappacificato con sua madre e non è più depresso. Questo basta, no?

Io le dissi di farsi fare una lingua finta e di andare da lui con quella.Il mio terzo atto, invece, lo commissionai ad un omosessuale, sieropositivo, che tendeva al suicidio. Diceva che lo psicanalista non riusciva a guarirlo. Non sapevo che pesci prendere... alla fine gli dissi che era un problema di sangue, e che doveva imparare che il sangue si può curare. Gli dissi di andare in un mattatoio con un grande thermos e chiedere a qualcuno il permesso di aiutarlo ad uccidere una vacca; poi di portarsi via tutto il sangue e di farcisi una doccia. Così fradicio, doveva montare su un pallone aerostatico con una foto di se' piccolo, e gettarla giù insieme a dei confetti. Mi guardò scioccato... ripeteva le mie parole dicendo: "E' impossibile! Dove lo trovo un pallone aerostatico?" " Se lo vuoi fare, lo fai", gli dissi. Poi incontrò una persona a cui raccontò tutto, persona che gli disse di essere il figlio del direttore del mattatoio. In seguito scoprì che i palloni aerostatici possono essere affittati da chiunque, ed è riuscito a compiere il suo meraviglioso atto panico. Non dico di avergli curato il sangue, ma la depressione se n'è andata, vive la sua sessualità con gioia, si è rappacificato con sua madre e non è più depresso. Questo basta, no?La soluzione a un problema può essere molto difficile, teatrale, facile.

Nella vita ci sono molti problemi: spesso non ho la forza di scrivere, soprattutto se devo scrivere di un argomento delicato: allora profumo la suola delle mie scarpe, così quando cammino le mie impronte aromatiche mi mettono il buonumore, il mondo cambia aspetto.

Nella vita ci sono molti problemi: spesso non ho la forza di scrivere, soprattutto se devo scrivere di un argomento delicato: allora profumo la suola delle mie scarpe, così quando cammino le mie impronte aromatiche mi mettono il buonumore, il mondo cambia aspetto.Che cosa ti ha dato Pachita?

Come giustifichi il fatto che il suo metodo di guarigione è passivo, mentre il tuo è attivo?

La psicomagia è l' evoluzione della magia popolare; ogni anno vado in Messico e visito i ciarlatani della città: conosco Pachita, Dona Paz... conosco molta gente, seria e non. Ma tutti, quello che fanno lo fanno con la fede. Non so se quello che usano sia o no vero sangue di gallina, ma non importa: la fede è ciò che agisce.

Io, invece, non voglio che si creda a quello che faccio: io spiego ciò che faccio. Non è superstizione, non sono io il mago: io ti dico cosa fare, il mago sei tu. La magia popolare si rivolge alla nostra parte più primitiva, istintiva: e infatti pretende la fede. La psicomagia si rivolge al cervello, impone un' azione: la fede passa in secondo piano. Tu sai ciò che ti accingi a fare... niente ti potrebbe far credere che quel sangue è caduto dal cielo: proviene da un animale che hai visto: è solo una metafora.

Però io ho appreso molto da Pachita, è una donna meravigliosa. E' una vecchia brutta, gobba, con un occhio storto. La prima volta che la vedo mi dice: "leggimi una poesia." E tutt' un tratto diventa uomo, e con un vocione "Sono qui!",dice, "sdraiati! Ti devo aprire il fegato!", ed io "No, aiuto!" ..."Ti apro qui!"... e mi apre! Che dolore, è terribile! E lei tira, tira fuori... poi fa un gesto come per cucire e il dolore se ne va. Mi offre la mano, io la prendo e con la mano le chiedo, e lei mi dà, io le chiedo, lei mi dà... io le chiedo senza limiti e lei mi dà senza limiti .. perchè il dolore non ha limiti. A fatto compiuto, mi guarda e mi dice "Prenditi un caffè"! La prima volta che l' ho vista c' era molta gente ed io ero molto timido, seduto in disparte... lei mi chiamò a sè dicendo: "Vieni qui, non avrai mica paura di una povera vecchia?". Non sapevo che fare. Tutti mi dicevano più volte: "Accetta il dono, accettalo!". Lei aveva la mano protesa... io le avvicinai la mia e vidi qualcosa che luccicava nel suo palmo... lo presi.. era un triangolo con un occhio in mezzo, un simbolo che le era apparso lì, sulla mano. Un simbolo che io non avevo visto... in mano non aveva niente: o era una maga, o una prestigiatrice o altro che non so, ma non è importante.

Però io ho appreso molto da Pachita, è una donna meravigliosa. E' una vecchia brutta, gobba, con un occhio storto. La prima volta che la vedo mi dice: "leggimi una poesia." E tutt' un tratto diventa uomo, e con un vocione "Sono qui!",dice, "sdraiati! Ti devo aprire il fegato!", ed io "No, aiuto!" ..."Ti apro qui!"... e mi apre! Che dolore, è terribile! E lei tira, tira fuori... poi fa un gesto come per cucire e il dolore se ne va. Mi offre la mano, io la prendo e con la mano le chiedo, e lei mi dà, io le chiedo, lei mi dà... io le chiedo senza limiti e lei mi dà senza limiti .. perchè il dolore non ha limiti. A fatto compiuto, mi guarda e mi dice "Prenditi un caffè"! La prima volta che l' ho vista c' era molta gente ed io ero molto timido, seduto in disparte... lei mi chiamò a sè dicendo: "Vieni qui, non avrai mica paura di una povera vecchia?". Non sapevo che fare. Tutti mi dicevano più volte: "Accetta il dono, accettalo!". Lei aveva la mano protesa... io le avvicinai la mia e vidi qualcosa che luccicava nel suo palmo... lo presi.. era un triangolo con un occhio in mezzo, un simbolo che le era apparso lì, sulla mano. Un simbolo che io non avevo visto... in mano non aveva niente: o era una maga, o una prestigiatrice o altro che non so, ma non è importante.Avrebbe potuto darmi qualsiasi cosa, ma mi ha dato un triangolo con un occhio dentro, quello che volevo.

Una volta le portai un grande maestro di karate che aveva la tendinite e non riusciva a curarla. Lui non credeva, ed entrò sicuro di se'. Lei gli sferrò un colpo accompagnandolo con un grido, e lo fece volare tre metri indietro.

Adesso lui crede!

Una ballerina aveva una gamba più corta dell' altra e Pachita le disse che l' avrebbe aperta per inserirle l' osso mancante e riallungarle l' arto. La vecchia portò a termine l' operazione e sei mesi dopo la ballerina mi chiamò per dirmi che stava ballando a New York e che l' andassi a vedere: quando arrivai là mi accorsi che teneva il piede rialzato, e che solo per questo non zoppicava più! Pachita non aveva allungato la sua gamba, ma la cosa importante è che lei aveva avuto fede: era cambiato il suo modo di vedere il problema. Allora ho cominciato a praticare la psicomagia: ho capito che non è necessario il miracolo fisico, ma l' atteggiamento mentale.

Una ballerina aveva una gamba più corta dell' altra e Pachita le disse che l' avrebbe aperta per inserirle l' osso mancante e riallungarle l' arto. La vecchia portò a termine l' operazione e sei mesi dopo la ballerina mi chiamò per dirmi che stava ballando a New York e che l' andassi a vedere: quando arrivai là mi accorsi che teneva il piede rialzato, e che solo per questo non zoppicava più! Pachita non aveva allungato la sua gamba, ma la cosa importante è che lei aveva avuto fede: era cambiato il suo modo di vedere il problema. Allora ho cominciato a praticare la psicomagia: ho capito che non è necessario il miracolo fisico, ma l' atteggiamento mentale.Una volta conoscevo una ragazza bellissima la cui madre era brutta, e per questo si era sottoposta a diversi interventi di chirurgia plastica. Sempre la madre aveva detto alla figlia di essere molto più bella di lei.

Così la bellissima ragazza corse da me piangendo perchè era brutta. Era bellissima, ma la sua mente l' aveva resa brutta, per colpa della madre. Se lei si fosse accettata bella, avrebbe perso la madre, perché viveva sempre con sua madre davanti al volto. Se invece si fosse accettata bella, avrebbe vinto sulla madre ma l' avrebbe persa: è molto più spiacevole perdere la madre che essere brutta. Le persone preferiscono ciò che è più piacevole, e ciò che è più piacevole può essere il meno spiacevole.

Così la bellissima ragazza corse da me piangendo perchè era brutta. Era bellissima, ma la sua mente l' aveva resa brutta, per colpa della madre. Se lei si fosse accettata bella, avrebbe perso la madre, perché viveva sempre con sua madre davanti al volto. Se invece si fosse accettata bella, avrebbe vinto sulla madre ma l' avrebbe persa: è molto più spiacevole perdere la madre che essere brutta. Le persone preferiscono ciò che è più piacevole, e ciò che è più piacevole può essere il meno spiacevole. Quando non si ha niente di piacevole, si sceglie ciò che è meno spiacevole.

Quando non si ha niente di piacevole, si sceglie ciò che è meno spiacevole.Io sono innamorato di mio padre o di mia madre: il rapporto incestuoso non può e non deve avvenire, quindi mi faccio venire un cancro e combatto con quello... come se fosse più facile farsi venire un cancro che combattere con il problema.

Perchè quelli che curano la gente, specialmente in Brasile, sono persone più o meno primitive?

Le persone che curano sono primitive... beh, è ancora un problema di fede e di superstizione: la gente ha bisogno di credere. Io non lavoro come uno sciamano, perchè lo sciamano usa droghe, che servono per entrare in un' altra dimensione mentale.

Ma in Brasile non usano droghe per queste cose...

Beh, se lei dice così... il maestro è caduto dal trono... è meraviglioso... chiudiamo così l’intervista.

::: FILMOGRAFIA :::

Abelcain 1999

The Rainbow Thief 1990

Santa Sangre - Sangue Santo 1989

TUSK1978

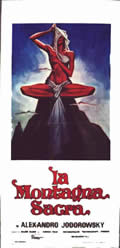

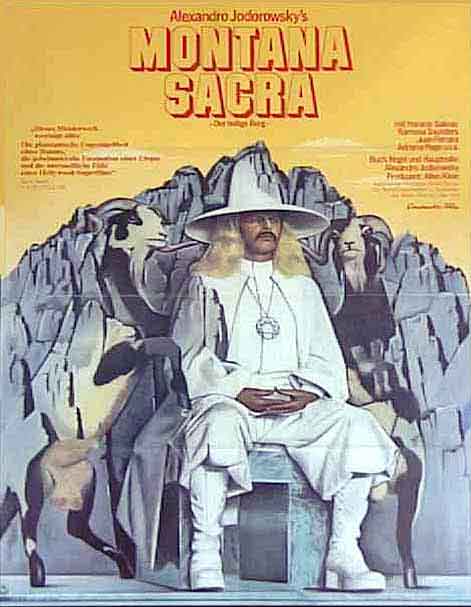

La Montagna Sacra1975

Il paese incantato1972

El Topo1971

Fando y Lis1967

The Severed Head 1955

Director Alejandro Jodorowsky

Director Alejandro Jodorowsky

Born in 1929 in Chile to Russian-Jewish immigrants owners of a dry-goods store, Alejandro Jodorowsky seems an unlikely candidate to become one of the godfathers of the American midnight-movie scene. But essentially every turn in his career has been unlikely, a career that's found Jodorowsky taking on the roles of director, screenwriter, author, actor, cartoonist, editor, artist, composer, mime, guru, mystic, and tireless self promoter. A famed raconteur, it's occasionally difficult to sort the facts of Jodorowsky's early life from the myth. Entering the theater at an early age, Jodorowsky eventually enrolled at the University of Santiago, where he developed an interest in puppetry and mime. After creating a theater company that employed 60 people at its height, Jodorowsky departed for Paris, breaking with his parents and (according to Jodorowsky) throwing his address book in the sea. Once in Paris he began a lengthy collaboration with Marcel Marceau, collaborating on some of Marceau's most famous mimeograms. He also worked both in mainstream theater (directing Maurice Chevalier's comeback) and in offbeat productions. For the next few years, Jodorowsky worked alternately in Mexico City and Paris, developing his interest in the avant-garde and staging the playwrights who would be major influences on his film career, including Samuel Beckett, Ionesco, August Strindberg, and the Surrealists. Of special importance would be "theater of cruelty" champion Antonin Artaud and Spanish playwright Fernando Arrabal, with whom he launched the Panic movement (from the god Pan) in conjunction with artist Roland Topor. By the mid-1960s, the Panic movement began yielding full-fledged "ephemeras" or "happenings," theatrical events designed to be shocking. One four-hour ephemera starred a leather-clad Jodorowsky and featured the slaughter of geese, naked women covered in honey, a crucified chicken, the staged murder of a rabbi, a giant vagina, the throwing of live turtles into the audience, and canned apricots.  This privileging of the provocative above all other qualities would prove to be a sign of things to come in Jodorowsky's early film career. In 1967, while working in the theater as one of Mexico City's most in-demand directors and concurrently turning out a comic strip entitled Fábulas Pánicas, Jodorowsky first tried his hand at directing a film. For his first project, he chose to adapt the Arrabal play Fando and Lis, which Jodorowsky had recently staged. Working on weekends from a one-page outline and his own memory of the script, Jodorowsky shot the story of two quarrelling lovers looking for the magical city of Tar. Fando and Lis was banned in Mexico after starting a riot at the 1968 Acapulco Film Festival, an event that forced Jodorowsky to flee an angry mob in a limousine. The film resurfaced to poor response in New York in 1970, garnering unfavorable comparisons to Fellini Satyricon. It wouldn't take long for the pain of rejection to wear off. In December 1970, Jodorowsky premiered his next film, the self-starring El Topo, at a midnight screening at the Elgin Theater in New York, bypassing the tumultuous Mexican scene entirely. Ignoring criticism that Fando and Lis owed too much to other directors, the nightmarish

This privileging of the provocative above all other qualities would prove to be a sign of things to come in Jodorowsky's early film career. In 1967, while working in the theater as one of Mexico City's most in-demand directors and concurrently turning out a comic strip entitled Fábulas Pánicas, Jodorowsky first tried his hand at directing a film. For his first project, he chose to adapt the Arrabal play Fando and Lis, which Jodorowsky had recently staged. Working on weekends from a one-page outline and his own memory of the script, Jodorowsky shot the story of two quarrelling lovers looking for the magical city of Tar. Fando and Lis was banned in Mexico after starting a riot at the 1968 Acapulco Film Festival, an event that forced Jodorowsky to flee an angry mob in a limousine. The film resurfaced to poor response in New York in 1970, garnering unfavorable comparisons to Fellini Satyricon. It wouldn't take long for the pain of rejection to wear off. In December 1970, Jodorowsky premiered his next film, the self-starring El Topo, at a midnight screening at the Elgin Theater in New York, bypassing the tumultuous Mexican scene entirely. Ignoring criticism that Fando and Lis owed too much to other directors, the nightmarish

allegorical western  El Topo practically announced its debts to Fellini, Luis Buñuel, and Sergio Leone. If audiences minded, it didn't show; El Topo became a cult sensation and the first midnight-movie hit. After a few months of underground success, El Topo attracted the attention of the critics, who were fiercely divided. Pauline Kael and Vincent Canby fell firmly in the anti-Jodorowsky camp, but a number of publications embraced El Topo as a masterpiece. "El Topo is a quest for sainthood," Jodorowsky claimed, but it was also a highly unpolished piece of filmmaking not above exploiting violence for kicks, and throwing in copious amounts of misogyny and voyeuristically staged lesbian sex. Regardless of the split, the film played on as a midnight sensation in a theater thick with eager fans and marijuana smoke. Time has been less kind. Unlike other midnight movies -- such as the work of John Waters and George Romero -- El Topo's reputation hasn't grown over the years, perhaps because it's a film virtually inseparable from the moment that produced it, a blood-soaked counterculture parable for the post-1968, post-Altamont, post-Manson era. At the suggestion of John Lennon, El Topo was acquired by Allen Klein's Abkco Films. Abkco also produced the even more extreme follow-up Holy Mountain, which failed to build on the success of its predecessor. In 1975, Jodorowsky, now living in Paris, announced his next project, an adaptation of Frank Herbert's sci-fi epic Dune starring Brontis Jodorowsky,

El Topo practically announced its debts to Fellini, Luis Buñuel, and Sergio Leone. If audiences minded, it didn't show; El Topo became a cult sensation and the first midnight-movie hit. After a few months of underground success, El Topo attracted the attention of the critics, who were fiercely divided. Pauline Kael and Vincent Canby fell firmly in the anti-Jodorowsky camp, but a number of publications embraced El Topo as a masterpiece. "El Topo is a quest for sainthood," Jodorowsky claimed, but it was also a highly unpolished piece of filmmaking not above exploiting violence for kicks, and throwing in copious amounts of misogyny and voyeuristically staged lesbian sex. Regardless of the split, the film played on as a midnight sensation in a theater thick with eager fans and marijuana smoke. Time has been less kind. Unlike other midnight movies -- such as the work of John Waters and George Romero -- El Topo's reputation hasn't grown over the years, perhaps because it's a film virtually inseparable from the moment that produced it, a blood-soaked counterculture parable for the post-1968, post-Altamont, post-Manson era. At the suggestion of John Lennon, El Topo was acquired by Allen Klein's Abkco Films. Abkco also produced the even more extreme follow-up Holy Mountain, which failed to build on the success of its predecessor. In 1975, Jodorowsky, now living in Paris, announced his next project, an adaptation of Frank Herbert's sci-fi epic Dune starring Brontis Jodorowsky,  Alejandro's son. Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, and Salvador Dali were also on board, but the film never got past the production stage. Almost as intriguing as the cast is the development talent Jodorowsky employed, which included writer Dan O'Bannon and artists Jean Giraud (a.k.a. Moebius), Chris Foss, and H.R. Giger. (All four would eventually work together on Alien.) Pink Floyd and the prog-rock group Magma were also reportedly on board to provide the score. If nothing else, the failed Dune project marked the start of Jodorowsky's long friendship and collaboration with Moebius, with whom he worked on a number of comic-book projects. His next film project, Tusk, told the family-friendly story of the bond between an English girl and an Indian elephant. The film remains rarely seen and Jodorowsky, citing differences with its producers, has disavowed it. Production difficulties included the fact that instead of receiving 1,000 elephants, he received seven; and instead of a budget of 5 million dollars, he received 1.5 million. By the end of the '80s, Jodorowsky's time seemed to have passed along with the counterculture that supported him. But in 1989 he staged a surprising comeback with Santa Sangre, a surrealistic horror film that attracted considerable cult interest. Produced and co-written by Claudio Argento (brother of Dario Argento),

Alejandro's son. Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, and Salvador Dali were also on board, but the film never got past the production stage. Almost as intriguing as the cast is the development talent Jodorowsky employed, which included writer Dan O'Bannon and artists Jean Giraud (a.k.a. Moebius), Chris Foss, and H.R. Giger. (All four would eventually work together on Alien.) Pink Floyd and the prog-rock group Magma were also reportedly on board to provide the score. If nothing else, the failed Dune project marked the start of Jodorowsky's long friendship and collaboration with Moebius, with whom he worked on a number of comic-book projects. His next film project, Tusk, told the family-friendly story of the bond between an English girl and an Indian elephant. The film remains rarely seen and Jodorowsky, citing differences with its producers, has disavowed it. Production difficulties included the fact that instead of receiving 1,000 elephants, he received seven; and instead of a budget of 5 million dollars, he received 1.5 million. By the end of the '80s, Jodorowsky's time seemed to have passed along with the counterculture that supported him. But in 1989 he staged a surprising comeback with Santa Sangre, a surrealistic horror film that attracted considerable cult interest. Produced and co-written by Claudio Argento (brother of Dario Argento),  it contained many moments of Jodorowsky's trademark for-its-own-sake bizarreness within a relatively coherent story and the handsomest filmmaking of the director's career. Despite a cast that included Omar Sharif, Peter O'Toole, and Christopher Lee, its follow-up, The Rainbow Thief, fared far less well and Jodorowsky seemed to disappear from filmmaking yet again, although he continued to conduct weekly seminars in his own self-styled amalgam of Jung and Tarot card-derived spirituality. In the late '90s, he announced plans to film Abelcain, a semi-sequel to El Topo, but due to copyright disputes with Klein, Jodorowsky was forced to change his protagonist's name from El Topo to El Torro.

it contained many moments of Jodorowsky's trademark for-its-own-sake bizarreness within a relatively coherent story and the handsomest filmmaking of the director's career. Despite a cast that included Omar Sharif, Peter O'Toole, and Christopher Lee, its follow-up, The Rainbow Thief, fared far less well and Jodorowsky seemed to disappear from filmmaking yet again, although he continued to conduct weekly seminars in his own self-styled amalgam of Jung and Tarot card-derived spirituality. In the late '90s, he announced plans to film Abelcain, a semi-sequel to El Topo, but due to copyright disputes with Klein, Jodorowsky was forced to change his protagonist's name from El Topo to El Torro.

An Interview with Alejandro Jodorowsky by Jason Weiss

Known above all as a film and theater director, Alejandro Jodorowsky (Chile, 1930) began by working in the circus and with marionettes. In 1962, with Arrabal and Topor, he founded the Theater of Panic in Paris, where they staged many happenings. His films, several of which have achieved cult status, include Fando y Lis (1969), El Topo (1971), La Montaoa sagrada (1973), Tusk (1979), Santa sangre (1989), The Rainbow Thief (1990) and Viaje a Tulún (1994). Not only was he the director, but he also wrote the screenplays, composed the music, and often acted in his films. A noted author of comic books as well, his work includes AnÌbal V, in Mexico, and the Inca Azul series with drawings by Moebius in France. Among his several novels, Donde mejor canta un pájaro (1994) offers an exuberant blend of magical realisms, in both the Yiddish and Latin American traditions, transforming his own genealogical tree into a story of myths and fables.

JW: First, a bit of chronology. When did you first arrive in Paris?

AJ: I arrived in Paris in 1953, from Chile. I first studied mime there, with Marcel Marceau's teacher, Etienne Decroux. A year later, I entered Marceau's company and I stayed five years. We traveled throughout the world, and I returned to Paris. Then, I also worked in music hall in Paris, I directed Chevalier. I was doing that for two years, it was very successful. After, I left for Mexico. During mystay in Mexico, I returned a number of times to Paris to found the Theater of Panic with Arrabal and Topor, and to do the efÌmeros (happenings). Then I returned to Mexico. After Mexico I was in New York for two years, and I made The Holy Mountain. Later, I went back to France. And for fifteen years now, I've been living in Paris, in Vincennes. But always traveling.

AJ: I arrived in Paris in 1953, from Chile. I first studied mime there, with Marcel Marceau's teacher, Etienne Decroux. A year later, I entered Marceau's company and I stayed five years. We traveled throughout the world, and I returned to Paris. Then, I also worked in music hall in Paris, I directed Chevalier. I was doing that for two years, it was very successful. After, I left for Mexico. During mystay in Mexico, I returned a number of times to Paris to found the Theater of Panic with Arrabal and Topor, and to do the efÌmeros (happenings). Then I returned to Mexico. After Mexico I was in New York for two years, and I made The Holy Mountain. Later, I went back to France. And for fifteen years now, I've been living in Paris, in Vincennes. But always traveling.

JW: What attracted you to Paris?

AJ: It was always a question of work. I wanted to do mime, and the only school for mime in the 1950s was Marceau's in Paris. And later, I would get calls to do a film or to do theater. In the last fifteen years, I decided to give a conference every Wednesday, to create an individual university which I called Cabaret Mistico. It was always full. So, from that moment on I gave tarot classes, I did studies on what I call psychogenealogy--I study the genealogical tree of the person, it's like a collective therapy, psychomagic, they're therapies--I wrote books. And I had quite a large following. So I stayed in Paris because it's always been full there to this day.

JW: Where did you do this work?

AJ: Different places. Sometimes in a school of mime, later for a long time in the university at Jussieu, and now I do it in part of a space I own which is a dojo for karate.

AJ: Different places. Sometimes in a school of mime, later for a long time in the university at Jussieu, and now I do it in part of a space I own which is a dojo for karate.

JW: How did you advertise it?

AJ: I never advertise it, since I started, and it's free. At the end people make a collection to pay for the space, like in a church. But it's by word of mouth, there's never been any publicity in fifteen years. Because I decided precisely to show that what people think is necessary, is not.

JW: Did Paris signify something special, something magic for you before you went?

AJ: Yes, because in Chile the important thing at that time, in the '40s and '50s, was poetry. There was Neruda, and Huidobro. Vicente Huidobro, his mother had a literary salon in Paris, and he was quite well known there. So all of us Chileans went to Paris as to the literary center of the world and of poetry. It was a myth. So of course I went to Paris for that.

JW: Did you meet Huidobro when you were young?

JW: Did you meet Huidobro when you were young?

AJ: No, Huidobro was already dead when I started in literature. I met Neruda, Nicanor Parra, in Chile. They were my masters in poetry. And Enrique Lihn, he was a great friend and my teacher, a great poet.

JW: When you arrived in Paris for the first time, did it correspond to your image of the place?

AJ: It was terrifying, because Chile is a small place and also I came without much money. And I arrived without speaking a word of French. The first day I ate a sandwich jamun--sandwich jambon--and then in the market I would point with my finger to the fruit I wanted. I learned French in the street, see. So Paris was very impressive, it still is. For a while I think New York was more powerful culturally, probably in the '80s or the '70s it was, but not anymore, Paris has a tremendous cultural development at this point.

JW: When you arrived in '53, whom did you know?

AJ: When I arrived existentialism was going on, and since I'm an explorer I really got involved with the last remnants of the existentialists, this was before hippies. I was really in contact with the existentialist core, people who were like the punks of that time.

JW: How did you find them?

AJ: By chance, they'd be walking around Saint Germain des Prés. There was a Chilean, who went about doped up on something called élixir parégorique. Paregoric was for diarrhea, it had a lot of opium. So he would buy medicines and take them by the liter. You can imagine the kind of person he was. So, he introduced me to that group, which I didn't belong to because you had to get drunk and high all day long. It wasn't for me, I was a mime, it was no help to me. But it was the first type of people I met in Paris. That is, people who must be legends now. After, I thought to go over to the Rue Cujas by the Sorbonne, where the great myth of the Sorbonne was Gaston Bachelard. It was very interesting meeting him. And in the same street the poet Nicolás Guillèn lived in exile, for example, you could run into him every day, or Violeta Parra, the singer, she was a friend of mine. They were the intellectuals who had been expelled from their countries. That was in '53, '55, up into the '60s. There was a place called L'Escale, on Rue Monsieur le Prince, where everyone went to dance and especially to meet French girls who liked South Americans. The only place where you could get yourself a French girl. We'd be there all night long. Latin Americans would come from all over to sing there, later the songs became quite famous.

AJ: By chance, they'd be walking around Saint Germain des Prés. There was a Chilean, who went about doped up on something called élixir parégorique. Paregoric was for diarrhea, it had a lot of opium. So he would buy medicines and take them by the liter. You can imagine the kind of person he was. So, he introduced me to that group, which I didn't belong to because you had to get drunk and high all day long. It wasn't for me, I was a mime, it was no help to me. But it was the first type of people I met in Paris. That is, people who must be legends now. After, I thought to go over to the Rue Cujas by the Sorbonne, where the great myth of the Sorbonne was Gaston Bachelard. It was very interesting meeting him. And in the same street the poet Nicolás Guillèn lived in exile, for example, you could run into him every day, or Violeta Parra, the singer, she was a friend of mine. They were the intellectuals who had been expelled from their countries. That was in '53, '55, up into the '60s. There was a place called L'Escale, on Rue Monsieur le Prince, where everyone went to dance and especially to meet French girls who liked South Americans. The only place where you could get yourself a French girl. We'd be there all night long. Latin Americans would come from all over to sing there, later the songs became quite famous.

JW: Were you looking to be with Latin Americans, or did you try to meet French people as well?

AJ: I'd end up with cases like El Greco, who was Argentine, he committed suicide writing the word fin in his own blood. He was one of the first conceptual artists, he filmed people in the street, he did a show where there were only white canvases... I met people like that. It was hard to meet French people. There was a big rejection from the French. So I was making friends with Latin Americans. I knew Marceau, of course, that was something else, and by way of him I managed to step outside of the Latin American world.

JW: What was your first encounter with André Breton?

AJ: I arrived in Paris around one in the morning, and from a café on Saint Germain called the Old Navy I called him. I said, I've just arrived. He asked me who I was. I said Jodorowsky. He said, Who is Jodorowsky? I told him, A young man of twenty-four and I've come to revive surrealism, here I am. I want to see you. So he said, Come tomorrow, it's very late. I said, No, now. He insisted no, so I told him, It's not surrealist of you to not see me, so it shall never be, and I hung up. Years later, we became friends. But it was pitiful, I found myself with an old invalid. He was like a great puritanical functionary by the '60s.

JW: Did you consider your experience after Chile as exile?

AJ: In Chile I was doing fine, but I reached a point where I couldn't learn anything more. So I took a boat and never returned. I broke off. No one threw me out. So I never felt myself an exile, I could return whenever I wanted. But I did feel myself a foreigner throughout the world. That is, I left Chile in '53, and I returned in '90.

JW: Did you keep in touch with family there?

AJ: I left my family, I broke off with them. I would never see anyone again. I broke off with everything. It was like death. It was something else over there.

JW: There were never encounters with such people when they came to Paris?

AJ: Yes, there was, I could see them. But it wasn't important.

JW: Why did you break things off like that? For personal reasons?

AJ: It was metaphysical. I wanted to live without roots. I wanted to have an imagination without limits. I didn't want to have a nationality.

JW: In your work as a writer you were already writing poetry as an adolescent, and later you did a lot of theater. But when did you start writing novels, was it much later?

JW: In your work as a writer you were already writing poetry as an adolescent, and later you did a lot of theater. But when did you start writing novels, was it much later?

AJ: Always, but I didn't publish. I started publishing in Chile in '90, because they offered it to me. In Chile I was immediately a best-seller. But what is it to be a best-seller in Chile? And in the last three years I've started to be translated. So one could say I'm just starting.

JW: And when did you start as a director, rather young?

AJ: Yes, I directed marionettes. I was already quite well-known in Chile.

JW: A question about scandal, which you rather seem to like. Where did your taste for scandal come from?

AJ: Every artist wants to be well-known. When one is not well-known, a scandal is marvelous because everyone knows you. At the same time it's very hard. Scandal provokes censure, so you have to be able to put up with that. Scandal followed me, I never sought it out. Like in Mexico, I'd make a film, it caused a scandal, I'd do a play, it caused a scandal. Because of the limits of the country. Because the society wasn't ready.

JW: Did having that reputation in Mexico pose certain limits?

AJ: A lot. There came a moment when I left. Because they threatened me and my family with death. After, I returned.

I returned.

JW: But scandal in Mexico is not the same thing as scandal in Paris.

AJ: Because Mexicans like it. They adore scandal. The whole country takes an interest, the tabloids. Scandal in Mexico is a tradition.

JW: And it's not like that in France?

AJ: No, it's very difficult to cause a scandal in France. In Spain as well it's difficult. But the two are different. In France it's difficult because they're very Cartesian. In Spain because they have no limits, nothing surprises them anymore. After Franco they did everything, so nothing can surprise them. Arrabal caused a scandal, because he said he'd seen the Virgin Mary. He caused a scandal in reverse, he tried to pass for a saint.

JW: Why did you return to Paris fifteen years ago?

AJ: As always for reasons of my livelihood. I signed a contract to do a film, which didn't get made, they paid for my trip, my hotel. But then I stayed there after. I never chose Paris, only the first time.

JW: How was it returning to Paris? Were things very different?

AJ: Paris is a city that changes very little. One of the big differences about that city is the outskirts and the new buildings. But Paris itself is always the same. Now, wherever you go in the world today, you find the same change. Everywhere, be it Chile, Argentina, Paris, the only thing people think about is making money. The desire to confirm oneself economically everywhere, while other values count for less now, it's like that with the young and everyone else. But I'm very hopeful. For twenty years it's been like that, twenty years from now it won't be. Things keep changing, it'll be something else. I think the world is going to be more spiritual.

JW: Even without having the sense of exile, do you sometimes feel a certain nostalgia as a foreigner?

AJ: The thing is, I grew up as a foreigner. Look, my father was a Jew who tried to pass for a Russian. My mother was half-Russian, because a Cossack raped her mother, and she tried to pass for a Jew. So I was Chilean and not Chilean, because I was the son of immigrants. So I was trying to pass for a Chilean, but never completely. I was never anything. Therefore, the only exile I know is the exile from myself. Because I was never myself. The nostalgia I would have to get back to myself, what am I? But not what am I as nationality. What am I as a spirit without limits. I have limits. So each day I try more and more to go toward the anonymous which is precisely the impersonal. To try to be an impersonal person. I don't think in terms of cities now. I think of the planet. I don't think in terms of nationality. I think of human beings.

AJ: The thing is, I grew up as a foreigner. Look, my father was a Jew who tried to pass for a Russian. My mother was half-Russian, because a Cossack raped her mother, and she tried to pass for a Jew. So I was Chilean and not Chilean, because I was the son of immigrants. So I was trying to pass for a Chilean, but never completely. I was never anything. Therefore, the only exile I know is the exile from myself. Because I was never myself. The nostalgia I would have to get back to myself, what am I? But not what am I as nationality. What am I as a spirit without limits. I have limits. So each day I try more and more to go toward the anonymous which is precisely the impersonal. To try to be an impersonal person. I don't think in terms of cities now. I think of the planet. I don't think in terms of nationality. I think of human beings.

JW: Did you always feel this way?

AJ: Little by little I tried to. In the beginning when I arrived in Paris, every day I wrote a letter to Chile. For a year I wrote a letter to a girlfriend every day, telling her my impressions, living it as the great adventure of Paris. Until finally I got tired of it, I didn't write anymore, I told myself if I write, I don't live... But if you ask me, where do I want to die? I don't have a place, for me. The land where I'm going to die is the undertaker where they'll cremate me. Nothing else. I don't need a grave anywhere. Where should they throw my ashes? I don't know, they can eat them or make a cake, I have no desire for my ashes to be scattered anywhere particular. I say it sincerely. When you say to me, what is your nationality? I look deep inside me, and I don't have any.

JW: At what point did you come to this feeling?

AJ: Look, when I was fifteen, I tore up all my photos. In order to not have any memory of myself as a child or anything, and to not get attached to photos. Later, I broke with the country. Later, I'm in France, I left France. Later, I left Mexico. In every place I was going away, I was always escaping. Now I'm at the problem that I don't know anymore who I am, and where I'm going and what I'm going to do. I've got contracts for the next six months. After, I don't know. Now they're translating me as a novelist. I'm a success in France. I'm doing fine. I've always done fine. I'll be successful, they'll publish me. And then what? I'll do another. And then what? I'll do another. And then what? Or I'll do another film. And then what?

JW: Connected to the question of where you want to die is the matter of your archives, the work you've done. Where do you think they should be kept?

AJ: Anywhere, it's all the same.

AJ: Anywhere, it's all the same.

JW: Did you get along well with Latin American writers in Paris?

AJ: Yes, yes... I'd go eat with Jorge Edwards, for example. He's my friend, I've known him since I was a child. I also know García Márquez, I'd eat with him, it was nice. But not a deep friendship . . .

JW: And the fact of doing many different things, did that set you apart?

AJ: It did set me apart, because society is used to a person only doing one thing. In France they disparaged Cocteau because he did a lot of things, and yet Cocteau was brilliant. Now they're realizing that Cocteau was brilliant, they're discovering Cocteau. It seems the only one who was permitted to do a lot was Chaplin. So when you do everything they say you think you're Chaplin, or you think you're Leonardo da Vinci, those are the two examples. But those are prejudices. I think there shouldn't be limits. They're prejudices that come from having a nationality, or from having a diploma, or from having a label. But it's a mistake.

AJ: It did set me apart, because society is used to a person only doing one thing. In France they disparaged Cocteau because he did a lot of things, and yet Cocteau was brilliant. Now they're realizing that Cocteau was brilliant, they're discovering Cocteau. It seems the only one who was permitted to do a lot was Chaplin. So when you do everything they say you think you're Chaplin, or you think you're Leonardo da Vinci, those are the two examples. But those are prejudices. I think there shouldn't be limits. They're prejudices that come from having a nationality, or from having a diploma, or from having a label. But it's a mistake.